” She flashed her horrible, wicked eyes upon me and said, ‘Victory.’ “

— From The Magician’s Nephew

Now we get to what is, for me, one of the most compelling features about Jadis and Charn: The war with her sister.

[ You can read previous parts of this essay here: Part I, Part II, Part III ]

Lewis doesn’t say if the sister is older or younger, a twin, a half-sister or stepsister; he doesn’t say how the war started, or why. We know that one sister eventually holed up in the city of Charn (Jadis) while the other attacked it (the nameless sister) because, at the end, Jadis is on the stairs of the palace as her sister walks up, triumphant, to gloat her victory. But beyond that, we don’t know much and that’s just as well. The scenes in Charn, vivid as they are, are only a small part of a small book. But they’re the most memorable ones, for the fierce battle, the dying world, the titanic city, and the Deplorable Word, uttered by Jadis, that extinguishes all life from it forever.

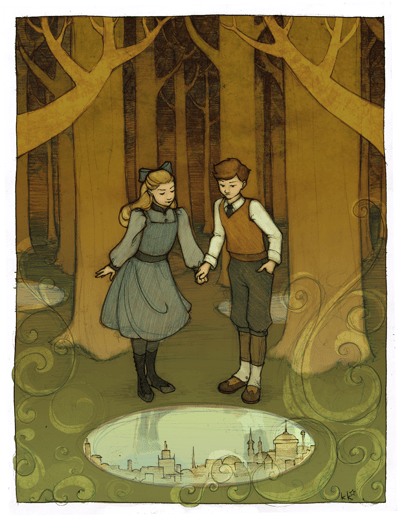

Jadis utters the Deplorable Word

The sparseness means there’s a lot of room there for imagination to room, as in these Charn fanfics.

We don’t know who was in the right, who was in the wrong in the conflict. Jadis tells us (through the story she tells to Digory and Polly) that it was her sister’s fault, for using magic when the two had promised not to… forcing Jadis to use magic in turn, and employing the Deplorable Word at the end when her defeat was clear. Yet, we can’t really believe Jadis is telling the truth, because of the self-serving nature of her tone, how she justifies her choices to serve her narrative of being the wronged, reasonable one. She might be fighting to save Charn from a more wicked ruler than herself, or fighting to keep Charn from a more judicious and enlightened one. We don’t know and we don’t have to know for the purpose of the story, which is to point out the futility of all wars.

(My take was always the rulers were twins, one dark haired, Jadis, one blonde and fair (sister) with their personalities matching their hair, as they did in old fairy tales. Sis wanted a less harsh and more humane rule, Jadis wanted to keep her boot down, so Sis ran away and raised an army, believing she was in the right. She had actually won, but for… )

It’s really a masterful turn by Lewis.

The peculiar thing about this tale of warring sisters is that it resonates so powerfully with the reader, more so than if Jadis were fighting her brother, one of her parents, or another relative such as a cousin. I thought it was due to historical precedent. But in my research I found there were, over the centuries, very few rivalries between female siblings for the throne.

One was Boran, who took the throne of the Sasanian Empire from her sister Azarmidokht (that’s a tongue-twister) during a period of civil war between the Persians and Parthians, with each faction supporting one sister over the other. The other female rivalry was between Cleopatra and her half-sister Arsinoe IV for the throne of Egypt, Cleo eventually aligning with Julius Caesar. Yet no one outside of Persian historians has heard of Boran, and Arsinoe isn’t even mentioned in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, the go-to guide for Egyptian political maneuvering in 16th and 17th century England. So where do the feuding sisters come from again?

The answer is right before us in the cradle of the English-speaking world: Elizabeth I and Mary I (more commonly known as Bloody Mary) who were half-sisters, and, after she became Queen, Elizabeth I and Mary Queen of Scots, who were cousins. All three women were ferocious combatants for power in the Tudor age, the core of their power struggles centering around religion – Protestant Elizabeth, who was to found the Church of England, vs. Catholic Mary I and Mary Queen of Scots. To the irreligious, it’s all rather silly; but very real for Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots, who endured periods of imprisonment and threat of death. Their story is one C. S. Lewis would have known well, as all English schoolchildren would. In the end, Elizabeth solved the problem by beheading her cousin, and not as coldly as one would think.

Cordelia’s Portion, by Ford Madox Brown, another pre-Raphaelite.

Goneril and Regan are glaring at each other over Lear’s right shoulder while Cordelia, dressed in light green to the right, gestures prettily.

The popular Shakespeare play King Lear also presents female rulers vying for power. The King, having divided his kingdom between his three daughters, sees two of them go to war over it while the third stays faithful to him, dying later after she and her father are captured. It’s a tragedy, and like a lot of Shakespeare very robust and adaptable – I have seen a version set in Shogun Japan, and another during WWI. Most college-educated Englishmen would be familiar with the play as well as the tale of Elizabeth and the Marys.

There are also many depictions of female rivalry from the fairy tales of Europe which Lewis praised so much, and if they were not warring Queens, they were warring rivals. Such as Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty and their stepmothers, and the Snow Queen and Gerda, to name a few. There were also likely many fantasy tales of powerful female rivals in early pulp magazines now crumbling to pieces; She by H. Rider Haggard, has been cited by Lewis scholars as an influence on the creation of Jadis, as Ayesha, the She of the title, vies with a native girl for a handsome explorer’s attentions.

Wraparound cover for the 1974 Ballantine paperback edition of The Lost Continent by Charles John Cutcliffe Wright Hyne

The similar pulp novel The Lost Continent contains a love triangle too, Empress Phorenice seeking to destroy her rival Nais for the love of the hunky Deucalion, former viceroy of Yucatan. It’s an upcoming project of mine to read the latter, and I can comment further on its influence on Lewis when I’m done. Both stories form the basis of a collective cultural memory that stretches from Victorian England up to Heavy Metal magazine, and beyond, to video games, manga, and anime, of women at war with each other.

And yet, there’s still something else that makes the Jadis-sister war resonate so strongly in the Chronicles, and it’s this: the sibling rivalry between Susan and Lucy. The rivalry was touched on in the first two books, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and Prince Caspian, and made clear in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by Lucy’s temptation over the beauty spell in the spellbook of Coriakin the magician. Not only that, there’s yet another female rivalry in the books, stated by the Beavers in LWW: that of Eve and Lilith, Adam’s first wife, who is said to be the ancestress of Jadis. The Jadis who infatuates Digory (at first, let’s note he wises up quickly) and causes Polly to deride her (” ‘Beast!’ muttered Polly. “)

These unspoken rivalries may be par for the era, in which girls and women were expected to compete for the best male possible to marry and procreate with, having few other choices in middle-class England among citizens of the “proper” class. But I also think it’s deeper than that. It’s an acknowledgement of the power of attractive, magnetic women with their own plans have over men, and the fear disguised as disdain they inspire in commonplace women who cannot or will not act the same way.

I will also note that traditionally in Lewis’s time countries were referred to as female – Britannia, Mother Russia, etc. – or shes, as boats and cars were. He must have absorbed that way of speaking and thinking as well.

At any rate, in Charn, Jadis had the last word.