thrum – thrum – thrum – thrum

The Lady of the Green Kirtle, sometimes known simply as the Lady, is the second major villain of the Chronicles of Narnia. She plays a star role in The Silver Chair, where she is responsible for killing Caspian’s wife and abducting his teenage son Rilian, using him in her plans for conquest. As I said here, she never got a proper name. I’ll call her the Green Witch for the purposes of this article.

In her illustrations for the book (one of which is pictured above) Pauline Baynes depicts her as anodyne, her expression sickly-sweet. That was part of the witch’s power, of course, to appear saccharine and harmless. She wears a long flowing Medieval gown, bright green in color, with wide scalloped sleeves. Plant sprigs surround her and adorn her hair; but they, and the green color, do not represent spring and new growth but poison and malice. Perhaps the plant sprigs are mistletoe, used as a poison by the druids. Whatever the plant is, it’s an invention of Baynes and not in the text.

Like Jadis, the Green Witch uses magic; but where Jadis is/was a Mage-Queen, the Green Witch is an Enchantress. She’s more overtly sexual than Jadis (even as Lewis did not get explicit about it) and uses her powers of physical attractiveness, beguilement, and disingenuousness to pursue her goals. As Jadis was based on the fairy tale character of the Snow Queen, the Green Witch is the La Belle Dame sans Merci, an alluring, magical maiden who causes chaos by toying with a knight’s affections, bringing him to self-destruction.

La Belle Dame sans Merci, by Frank Dicksee

This deadly lady was a popular subject for pre-Raphaelite painters, such as Frank Dicksee, who painted the above. I’ve always loved this picture. It’s so trite and silly, yet erotic, the way the woman, sitting sidesaddle on the knight’s charger, leans down to sweep the knight with her mane of long red hair, and he glances up, startled, the two round chest protectors by his armpits looking like aroused nipples. He’s flushed with excitement, while she is cool as ice.

The Kiss of the Enchantress by Isobel Lilian Gloag

This picture shows another alluring enchantress from the same era as she transforms into a serpent. As the knight succumbs to her kiss she begins to wrap her tail around his leg, trapping him, and reaches for his hand with a long, pale arm. But he fists it tightly, showing the viewer his resistance to the spell. This encounter could go either way, with him either being seduced, or breaking free.

The artist, Isobel Lilian Gloag, was one of the rare female pre-Raphaelites and I think this gives her watercolor more nuance. The witch’s desire here seems equal to the knight’s, but it may also kill him, by those coiled, thorny branches that sprout up by her tail, and I wonder if Lewis had seen this image somewhere and based the Green Witch on it.

Baynes’ illustration of the witch’s transformation is, interestingly, more into water creature than snake, going by the creature’s fins. She looks rather like an oarfish. Her tiny, narrowed eyes convey hate, and Lewis reveals some old fashioned courtliness in that it’s remarked by Rilian that it was easier to kill her in snake form than a human one. And by kill I mean kill: her head is hacked off and gore spews everywhere.

Illustration by Pauline Baynes

|

… the Prince’s own blow and Puddleglum’s [blow both fell] on its neck. Even that did not quite kill it, though it began to loosen its hold on Rilian’s legs and chest. With repeated blows they hacked off its head. The horrible thing went on coiling and moving like a bit of wire long after it had died; and the floor, as you may imagine, was a nasty mess. |  |

Ye Gods, even Jadis’s death happened off-screen.

Yet the reader can’t help cheering the butchery because the character was so vile. So vile that at the end even her gender and sentience are erased by Lewis’s use of it and thing. Even Rilian comments “… I am glad, gentlemen, that the foul Witch took to her serpent form at the last. It would not have suited well either with my heart or with my honour to have slain a woman.” (When I re-read this passage, I was also struck how Jill, but not Eustace, becomes sick to her stomach at the gore; in her next appearance in Narnia, in The Last Battle, the same thing happens when she sees Tash floating through the trees.)

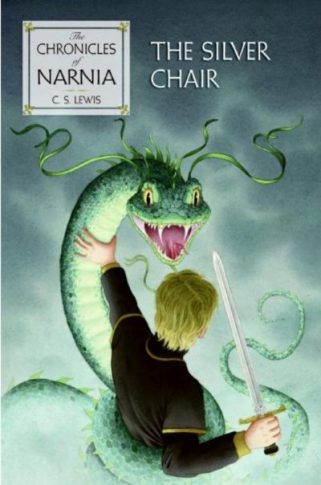

Other artists have taken on the witch’s transformation and attack but most of the covers look ridiculous.

Honestly, how menacing is a giant snake with ribbons in its hair? (Yes, I know snakes don’t have hair.)

Illustration for the cover of The Silver Chair, by Leo and Diane Dillon

This version by artists Leo and Diane Dillon does it better, showing the witch in mid-change. The Dillons also did this depiction of the White Witch as well as cover illustrations for the other five books of the series.

(Personally, I imagine the serpent looking more realistic, like this one, a Green White-lipped pit viper.)

The witch’s best scene, of course, comes before she is snaked, after Rilian, having been freed from the chair by Puddleglum and the kids, confronts her before the fireplace. She shows no anger, just throws a green powder into the flames and begins to casually strum on a mandolin while questioning the reality of her captives’ world. She doesn’t wale on them like Jadis would, through a whip or with brute strength, but with guile and subtlety. The passage ranks among the finest philosophical writing of all the series. When Puddleglum steps on the burning fire and extinguishes the smoke, saying his piece, the witch loses her cool and, in fury, becomes the serpent.

In this illustration the witch wields her mandolin like a weapon. Her hair is straight, not curled as in the text. She also looks pregnant, which frankly wouldn’t be beyond her machinations in a more adult story.

But the Green Witch is not overtly seductive. When Jill, Eustace, and Puddleglum encounter her on the road with the disguised Prince Rilian, she’s all charm and smiles, designed to make both genders feel at ease. The only warning sign is that she’s too charming for that rugged and foreboding place, as Puddleglum realizes: “Anyone you meet in a place like this is as likely as not to be an enemy, but we mustn’t let them think we’re afraid. […] Begging your pardon, Ma’am. But we don’t know you or your friend—a silent chap, isn’t he?—and you don’t know us. And we’d as soon not talk to strangers about our business, if you don’t mind.”

The witch agrees, insults him subtly, and lets it roll off her back with a tinkling laugh. She guesses at it anyway, recommending they stop at the House of Harfang for a long rest with the Gentle Giants, thus sowing the seeds of dissension among them.

In fact, if The Horse and His Boy was about the Christian sin of Pride, which Lewis scholars often say it is, The Silver Chair may be about the dangers of Sloth. The kids are far too easily taken in by promises of relaxation, and their minds (and more importantly, their spirituality) become lazy, falling prey to the Green Witch’s mesmerizing speech and her veneer of demure prettiness.

Lady of the Green Kirtle, by Kecky

This is why overtly sexual depictions of the witch don’t work for her character. She may be a conniving, powerful ball-buster, but on the surface, she’s wholesome and innocent. Which is what makes her character so disturbing, IMO. She’s a form of psychopath. It’s even hinted earlier that Rilian’s mother, Ramandu the Star’s Daughter (who really deserves a name) realized the truth about her, but died of the poison before she could warn her son. Rather an ignoble and meangingless end for her. But the Chronicles are actually full of these, much more so than The Lord of the Rings trilogy, fellow inkling Tolkien’s work. There, only the villains and nameless extras die, save for Boromir and Theoden, who both get noble and heroic demises, and Denethor, whose suicide was full of epic tragedy.

To give the Green Witch a throne room, like this concept artist for shelved Silver Chair movie did, is out of character as well.

Though an interesting, colorful design with swamplike elements such as fungi, it doesn’t fit the story. The Green Witch wasn’t showy or splashy. She didn’t need to impress. She was perfectly capable of creating her own slavish followers through magic. She didn’t need an elaborate set.

Artwork by Sumimasen

Although she was, perhaps, even worse of a villain that Jadis, Lewis did have some dark, wicked fun with the Green Witch’s character, poking fun at her the same way he did with Jadis’s fish-out-of-water turn in Edwardian London. The Lady appears charming and courtly on the surface, but she’s also slightly grating. Her speech is affected (that trilling which is odd to modern readers, but likely made sense in a Medieval world) and, especially, her milquetoast, condescending tone. It’s how a child would conceive Medieval speech, and it sounds false. Lewis employed the same trick at the end of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe with the speech of the adult Pevensie monarchs (“Marry, a strange device,” said King Peter, “to set a lantern here where the trees cluster so thick about it and so high above it that if it were lit it should give light to no man.”) which, as a child, I hated — mainly because I couldn’t understand it — but it also made them into different characters from the four kids I had just read about. But it was also genius on Lewis’s part, because when they pass the lamppost and enter the wardrobe they turn back into their old selves. I think Lewis really meant for them to sound stilted and ridiculous, so when they return to 1940s England the reader breathes a sigh or relief that they’re back and has no regrets they lost out on Narnia.

The same element is at play in the witch’s and Rilian’s speech, the Medieval tone both mocking and concealing what is underneath. When Rilian returns to his true self his speech is not so flowery anymore. Lewis plays homage to Arthurian tales while also making fun of them, the same way he paid homage to H. P. Lovecraft in his depiction of the ruined city of the giants and stone bridge earlier in the same book.

Temptation, by Fabio Pratti

The more adult connotations of the story are left unstated. Yet, to an adult they’re obvious. Rilian and the Green Witch look like they’re having a stereotypical courtly relationship, the chaste knight-protector and high-born lady love; but surely sex is also part of her control over him. The tale of Rilian’s disappearance, related by an elder Owl, attests. Not only is he her lover, he is slavishly devoted to her, which the kids make fun of (“He’s a great baby, really: tied to that woman’s apron strings”). It must have been a hoot for Lewis to write how modern kids would react towards goopy courtly love.

After the witch’s death, Lewis is careful to point that the two horses she and Rilian rode on, Snowflake and Coalback (left) are saved from the Underworld and return to Narnia with the good guys. The horses are innocents in all of this. It’s also a way of saying the nightmare is over and normal life can go on.

5 pings

[…] Some were referred to by a certain item of dress, like C. S. Lewis’ character pastiche The Lady of the Green Kirtle in The Silver Chair, or even by what they lacked (The Beautiful Lady Without […]

[…] parts of the series can be read here (Part I) and here (Part […]

[…] because it contained arsenic that tended to poison its users. (Another reason C. S. Lewis named his Green Witch as he […]

[…] parts of this series: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part […]

[…] parts of this series: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV, Part […]